Faith in action: Church’s compassionate aid for migrants in Spain

Vatican news

Catholic-inspired organizations are implementing a series of social programs in Ceuta and Algeciras, assisting those arriving from Africa to enter Europe. One of the greatest challenges is the fight against human trafficking which exposes women to forced prostitution.

By Felipe Herrera-Espaliat, Special Correspondent in Ceuta and Algeciras

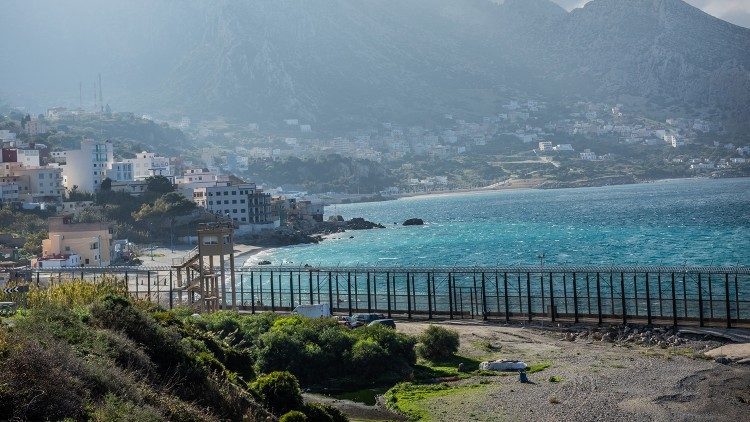

Ceuta is a Spanish city, but it is located in Africa, in northern Morocco, at the Mediterranean entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar. It is a strategic territory not only for Spain but also for the thousands of African migrants trying to enter Spain each year, setting foot in Europe for the first time. But since 2020, when circulation through the border was heavily restricted, posing significant obstacles to the flow of people, everything has become more difficult.

An eight-kilometer-long and ten-meter-high fence serves as a barrier between the two countries, a fence that hundreds of people try to climb over every day. Many succeed, but then they are arrested and immediately repatriated to Morocco or, in the best cases, taken to immigrant detention centers. Others, taking greater risks, bypass this wall by swimming for an average of four hours from the Moroccan coast to the shores of Ceuta. Those who do not die in this attempt arrive exhausted, soaked, and bereft of everything, trembling not only from the cold but also from the fear of being discovered by the police.

And the risks do not end there, especially for women who, often deceived with false promises of work, fall into the hands of human trafficking networks that force them into prostitution. They end up living in apartments that are both their accommodation and the brothel from which they can only leave for a couple of hours a day, under the strict control of the “mafia” that has abducted them.

Doubly vulnerable

In Ceuta, there are Catholic Church organizations that are active in the fight against human trafficking, such as the Cruz Blanca Foundation. Among its many assistance programs for those in need and for migrants, its initiatives to save women who have been forced into prostitution stand out. Its members visit them in brothels with healthcare supplies and, in doing so, come into contact with them.

Irene Pascual, a social worker for this institution, knows the trafficking victims very closely. She personally follows many of them to provide guidance and support so they can leave that situation. She says it’s not easy at all because the exploiters take advantage of the fact that these women don’t speak the local language and don’t have support networks. “A woman is a doubly vulnerable: being a migrant and being a woman. Women don’t see another way out when they arrive in a country they don’t know. The only way they see to move forward is to engage in prostitution,” explains Irene.

Segregation in “El Príncipe”

This foundation, with 20 assistance centers in Spain, is led by the religious community of the Franciscans of the Cruz Blanca (White Cross) and managed by highly qualified teams to address the challenges posed by poverty and by the current migration crisis. “Migrants arrive with very different needs, and various professional figures help identify these specific needs. We brothers team up with them, and are willing to work 24 hours a day every day. All this for the love of God,” assures Brother Cosmas Nduli Ndambuki.

The headquarters of this organization in Ceuta is in the “El Príncipe” neighborhood which is considered one of the most dangerous areas, not only in the city, but in the whole of Spain. It is located very close to the border and is inhabited almost entirely by Muslims from Morocco, who have filled the area with mosques. Among this population is the highest concentration of people without legal documentation and who cannot work legally or access social benefits. This is the case of Omar Layadi, a barber who has lived there for 16 years. Since neither he nor his wife have a residence permit, their three-year-old son, who was born here, cannot obtain one either and lacks legal recognition because there is no Moroccan consulate in Ceuta. Despite everything, Omar says he prefers to remain in these conditions in Spain rather than return to Morocco. “Here work and life are better. I have many friends, many clients, and my family. I have everything here,” he says.

Nayat Abdelsalam, a Spanish woman of Moroccan origin and a Muslim community leader, has collaborated with organizations of the Catholic Church to address the migration crisis. As a resident of “El Príncipe,” she knows, first-hand, the needs of her neighbors and fights for policies that counteract the territorial segregation to which Muslims have been subjected, as well as the lack of social rights. “Those who have not regularized their situation have no help at all. They can access a food bank offered by the Church, or a meal, but there is no aid, nor projects or programs for these kinds of people,” denounces Nayat.

Increasingly young migrants

Across the Strait of Gibraltar, 44 kilometers away, is the port of Algeciras, where another team from the Cruz Blanca Foundation provides support to those who have already entered the European continent but remain vulnerable. Just over a year ago, it welcomed Abdeslam Ibn Yauch, a 31-year-old Moroccan who worked as a painter and laborer, a profession he hopes to practice in Spain once he obtains a residence permit. In the meantime, he is taking technical courses and helping arriving migrants, mostly young people. “Migrants are now very young, and their main concern is to work to be able to help their mothers. I think the deepest wound they carry with them is having left their families behind,” explains social worker Mayte Sos, describing the type of migrants who knock on the door of the Cruz Blanca.

That’s where, Awa Seck, a 42-year-old Senegalese woman who lived in Mauritania for a long time for work, was also rescued. Three years ago, she decided to emigrate even further from her family and arrived in Algeciras, hoping to find a job that would allow her to more easily provide food, clothing, and education for her children, who remained in Senegal with her mother. “I came here to change my life, to find a good job,” explains Awa with pride, because she is achieving her goals. Today she has a residence permit, as well as a job in the culinary sector, and is saving money to bring her family to live with her.

Both in Ceuta and Algeciras, those who are part of the interdisciplinary teams of the Cruz Blanca know that their mission reaches far beyond mere legal, health, or social assistance to migrants. Professionals and volunteers seek above all to give dignity to those who, often desperately, ask for help. Their life stories are full of traumas experienced in their countries of origin and the pain of separation from their loved ones, but also of hope for a better future. Friar Giovanni Alseco, a Franciscan Brother of the White Cross, emphasizes that the great objective of this foundation is to be a family that welcomes, accompanies, and transforms. “We put into practice the Gospel of the Good Samaritan, always at the total service of those most in need, and we always seek to fill the lives of others with joy,” concludes the religious.

This reportage was produced in collaboration with the Global Solidarity Forum.

Vatican news

sc