Archbishop Peña Parra misled about London contracts

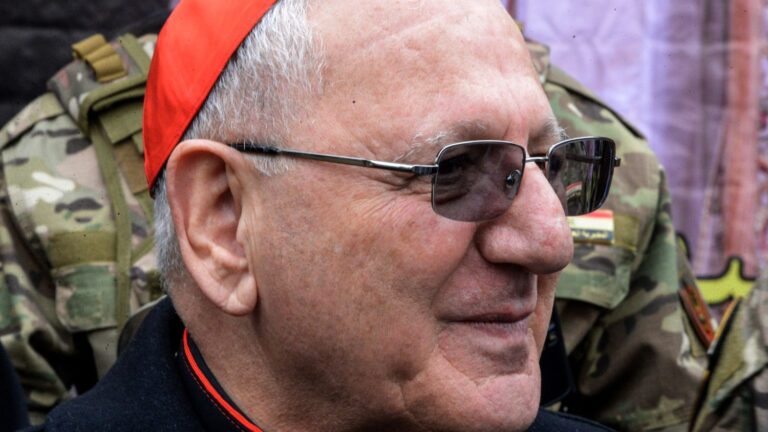

At the second hearing of the High Court of Justice in London concerning the Sloane Avenue property case, the focus is again on the relationship with the broker Gianluigi Torzi. Archbishop Edgar Peña Parra reiterates that he would never have ratified the agreements with the financier Raffaele Mincione and Torzi if he had been properly informed.

By Salvatore Cernuzio – London

“Your Honor, from that point on, our decision, our will was to get out of this situation. I knew it and everyone involved knew it… the 5 million was part of the delicate things, “But we were forced to do it, for what? For freedom, to be free from these people, to finally be free. That's the problem. We had no other choice. Even the Holy Father told me to try to lose as little as possible and to turn the page.”

“Traps”

The relationship with broker Gianluigi Torzi and other figures described as “wolves in sheep’s clothing” who gravitate around the Vatican were at the heart of the second questioning of Archbishop Edgar Peña Parra, the substitute for the Secretariat of State. The questioning, which lasted all day, took place at the High Court of Justice in London. As in yesterday’s first hearing, the questioning was conducted by Raffaele Mincione’s lawyer, Charles Samek, whose lawsuit triggered the ongoing civil trial that began on June 24. As in Thursday’s hearing, there was no mention of the transactions with Mincione, the manager of the fund that owned the Sloane Avenue building. The focus was mainly on the transactions with Torzi (condemned in the first instance by a Vatican court), to whose Gutt fund the management of the building had passed thanks to an agreement granting the broker a thousand shares with voting rights, therefore total control of the building. Archbishop Peña Parra called this situation a “trap” that forced the Holy See, after a series of pressures and even threats from Torzi (such as selling the property to third parties or using the income to finance his businesses), to pay the 15 million euros that he demanded to end all relations. The payment was made in two installments of 10 and 5 million, certified by invoices demanded by Torzi, partly referring to “consultations” that never took place.

Forced to pay

In a longer period of time, Archbishop Peña Parra was able to better define the details of these operations that took place during the months of negotiations with the broker between the end of 2018 and the beginning of 2019, as well as the climate of pressure due to being, according to the Vatican judges, victims of a crime. “The 15 million should never have been paid,” the archbishop stressed. “We had already made another transaction of 40 million to be free, and after that, in December, I found myself in the same situation with Torzi, the thousand shares, the WRM (Mincione’s company, theoretically ousted from the business following an agreement in 2018) that manages the building, and we continue to pay 6 million a year. We were forced to pay and everyone in the Vatican knew me and supported me in this process.”

Negotiations with Torzi

During the long hearing – from 10:30 to 16:30, with a break – there was much discussion about why the negotiations with Torzi went from an initial settlement proposal of 1 or 2 million euros (“even those were too much”) to 9 million, and finally to the 15 million paid. According to Archbishop Peña Parra, the amount of 9 million was revealed after a meeting at the Bvlgari Hotel with the broker, Fabrizio Tirabassi and Enrico Crasso (respectively an employee and a consultant of the Secretariat of State, both convicted in the first instance). The archbishop said he learned of this meeting a few days later. It is known from what emerged from the Vatican trial that Torzi demanded up to 25 million euros for his management work and future lost earnings. Monsignor Mauro Carlino (the only one of the ten accused in the Vatican trial to have been acquitted) was sent to mediate with the broker.

Inform superiors

Regarding the contracts with Mincione and Torzi in November 2018, the Substitute of the Secretariat of State was repeatedly questioned as to whether he had informed his superiors, namely the Pope and Cardinal Secretary of State Pietro Parolin, of his actions, apparently to test his loyalty and trustworthiness. The Archbishop confirmed that he had always informed Pope Francis and Cardinal Parolin in advance of each action; for example, when he decided to contact the Auditor General, Alessandro Cassinis Righini, on Saturday, 24 November 2018, to obtain an opinion on the contracts for the London building, in particular the framework agreement marking the transfer from the Gof (Mincione) fund to the Gutt (Torzi) fund.

Auditor General's Opinion

“I want to emphasize,” the prelate said at the bar, “that this was the first time that a substitute had consulted the auditor general. It was not a tradition of the Secretariat of State, which has its autonomy. But despite this, I wanted to be sure of what we were doing. I had been in office for a month, I was still looking for where my chair was… I took an extraordinary measure that was certainly not a joy for the Administrative Office.”

Cassinis Righini responded to the Substitute on Monday, November 26, with a letter. The Pope and Cardinal Parolin were aware of this decision to consult “competent persons,” but Cassinis’ response was not sent to them: “No,” explained Monsignor Peña Parra, “because it was addressed to me, not to them. I was the only one concerned, I am the Substitute. And I was alone in this operation…”

Second document never received

Mincione's lawyer pointed out that there had been a second response from the auditor, who strongly advised against proceeding with the operations. “Why didn't the substitute take that advice into account?” Archbishop Peña Parra's response was direct: “I never received that document. I saw it during the trial at the Vatican.” Sent to the Secretariat of State, it arrived on some desks, but not on that of the substitute. “If I had received indications advising against the operation, that would have been the best gift, because I would have had the authority to say not to proceed,” the witness said. “I regret not having seen that document, otherwise I would not be here.”

The role of Squillace

Among a myriad of documents and names – all already mentioned in the 86 hearings of the Vatican trial – Friday’s session recalled the role of lawyer Nicola Squillace. Introduced to the archbishop as a lawyer for the Secretariat of State, with a group of collaborators who had worked with him for 10 to 30 years, Peña Parra also asked him for an opinion on those “thousand shares with voting rights.” What did they mean? It took another month for the Secretariat of State to learn from consultant Luciano Capaldo that the contracts stipulated in November with Mincione and Torzi, both signed by Archbishop Alberto Perlasca (“without authorization”), had led to the acquisition of “empty shells.” This prompted the pope to summon the Substitute to a meeting in Santa Marta, also attended by lawyers Manuele Intendente and Giuseppe Milanese, to clarify the situation. It was then that Archbishop Peña Parra understood that the situation was out of control.

“At the time, Squillace – recalled Peña Parra on Friday in room 19 of the Superior Court – had reaffirmed that the thousand shares only served to allow Gutt to enter the administration of the building.” After these assurances, the substitute ratified the signature of Monsignor Perlasca. “As soon as I arrived, I tried to do my best to have a clear idea of what was happening in the Secretariat of State. Nothing more than what was necessary…”

IOR Financing

During the hearing, the issue of the 150 million requested by Archbishop Peña Parra from the IOR to renegotiate the onerous mortgage of Cheyne Capital taken out by Mincione for the London property was addressed. An “internal” approach to prevent the Holy See from losing almost a million a month. The Institute for Works of Religion (IOR) had initially guaranteed the loan, but had withdrawn after a few months. The substitute was surprised: “Why the delay?” Even the director (Gian Franco Mammì) had assured him that everything was ready. Instead of the loan, a complaint from the IOR arrived, triggering investigations into this complex affair that bounced from Rome to London.

Peña Parra was asked if it was true that after the refusal he had contacted people close to the Italian secret services to monitor the IOR director, including through wiretapping. The phone had nothing to do with it, the witness clarified: “I asked the head of the gendarmerie to have a clear map of all the companies and entities that were in contact with us during that period. I wanted to avoid dealing with such people in the future.”